The Australian Gold Rush of the 1850s brought about many challenges for both miners and the communities they had left. After months away, droves of individuals would return to their respective towns, Adelaide included, with ample gold in tow. The necessity to process this gold became immediately apparent, and, under the Bullion Act of the Province, the Government Assay Office of South Australia was authorized. Prior to the striking of the instantly recognizable “Adelaide” Pound, the Assay Office issued gold ingots for the purpose of backing banknotes circulated by local banks. Ingots proved unsuccessful and were quickly replaced by (round) coins valued at 1 pound each, 22 carats.

History of the Ingots and the 1852 Bullion Act.

The Government Assay Office 1852 Gold Ingots are the very first gold pieces struck for currency purposes in the colonies of Australia, issued in South Australia under authority of the 1852 Bullion Act of the Province.

The Bullion Act was enacted on 28 January 1852 and remained in operation for twelve months. To ensure that the Government would have a steady supply of gold, its price was fixed for the duration of the Act at £3 11s per ounce.

The Ingots could be exchanged for banknotes at the rate of £3/11s per ounce. They could also be used by the banks to support their note issue, just as if they were gold sovereigns.

The discovery of significant gold deposits in Australia in 1851 created sudden wealth and stimulated immigration on a vast scale.

It had a profound impact on Australia’s social and political development and underpinned the abandonment of the penal system on which the settlement of Australia was based.

The new-found confidence and a vastly increased population encouraged a national sentiment that accelerated the Australian colonies to unite and form the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

It is one of the most eventful and extraordinary chapters in Australian history, transforming the economy and society and marking the beginnings of a modern multi-cultural Australia.

Word of the discovery of gold spread like wildfire across the country and overseas. First was the rush to Ophir near Bathurst in early 1851 and the even greater rush to Ballarat in August of the same year.

Then in quick succession came the rich finds throughout central Victoria, Queensland, Northern Territory and finally the bonanza in Western Australia.

No colony was immune from the dramatic effects of the discovery of gold.

Those that were rich in gold. And those, such as the colony of South Australia, that was devoid of the precious metal. Its economy collapsed due to the mass exit of manpower lured to the Victorian gold fields.

Adelaide lost almost half its male population within the first three months of the first big gold strike near Ballarat. Also gone its cash resources. About two-thirds of the available coin travelled out of the state.

As the two main pillars of national activity, labour and capital, literally walked out, prices plummeted, property plunged, mining scrip nosedived, and Adelaide took on the air of a ghost town, with row after row of tenantless houses.

The cash-strapped banks pressed their debtors for cash payments, but as most debtors were merchants with their capital tied up, disaster beckoned.

By late 1851, genuine panic gripped those who had stayed behind as the total and complete insolvency of Adelaide looked real.

Out of desperation the Government offered a reward of one thousand Pounds for the discovery of a gold field in South Australia. None was found.

South Australia’s problems were further compounded because there was no method available to convert the gold nuggets the diggers had brought back from Victoria into a form that could be used for monetary transactions.

Calls were made for the establishment of a Government mint and the issuing of a coinage, but this was viewed as being in direct violation of the Royal Prerogative. Coining was beyond the powers and privileges of any local authority.

On 9 January 1852, over 130 leading businessmen met with a further 166 merchants met with Lieutenant Governor Sir Henry Young and pressured him to start up a mint to convert the raw gold into coin. The intention was that the mint would purchase gold from the Victorian fields at a higher price than paid in Melbourne.

There are some doubts as to who suggested an Assay Office and stamped bullion. What is known is that the establishment of a similar office had been introduced into the legislature of New South Wales in 1851. It was defeated mainly due to the opposition of the banks.

What is also known. Robert Richard Torrens, the Colonial Treasurer, was an active and strong supporter of the proposal.

Although Young realised that only Royal approval could initiate a move to establish a mint, he was also aware that the survival of the colony was at stake.

He found a loophole in the legislation. While the Governors were not allowed to assent in her majesty’s name to any bill affecting the currency of the colony, an accompanying paragraph that stated … “unless urgent necessity exists requiring such to be brought in to immediate operation”.

The “urgent necessity” clause paved the way for the South Australian Legislative Council to pass the 1852 Bullion Act.

A special session of the Legislative Council was convened on the 28 January 1852.

An enactment was proposed that allowed the Assaying of gold into ingots; the Council seeking to deflect Royal disapproval by striking gold ingots rather than sovereigns.

The ingots were intended to form a currency that would back the banknote issues of the banks as if they were gold coin. And be used by the banks to increase their note circulation based on the amount of assayed gold deposited.

The Act was as daring, as it was contentious, in that it made the banknotes of the three South Australian banks a Legal Tender, under specified conditions.

It drew condemnation from the eastern states. Melbourne’s Argus condemned the Act as dangerous, radically unsound and interfering with the natural laws of commerce. But these protests were motivated by self-interest, as South Australia posed a real threat to the Victorian economy by re-directing capital and labour away from the Victorian gold fields.

The Bullion Act No 1 of 1852 has a record unique in Australian history. A special session of Parliament was convened to consider it. Parliament met at noon on the 28 January 1852. The Bill was read and promptly passed three readings and was then forwarded to the Lieutenant Governor and immediately received his assent.

It was one of the quickest pieces of legislation on record, with the whole proceedings taking less than two hours.

Thirteen days after the passing of the Act, on 10 February 1852, the Government Assay office was opened. Its activities were supported by a state government initiative to provide armed escorts to bring back the gold from the Victorian diggings.

By the time the first escort arrived, a second assay office had been established, and Joshua Payne was appointed die-sinker and engraver. By the end of August 1852, over £1 million worth of gold had been received at the assay offices.

The passing of the Bullion Act was a masterly stroke of legislature and played no small part in averting economic catastrophe and laying the foundation for a stabilised currency.

Leading numismatic author Greg McDonald expressed his views when he wrote. “That Australia is today viewed as one of the most desirable destinations on the planet is due, in no small part, in the ability of our forefathers to find an often analytical solution to a problem. The creation of these golden relics is a part of that ”can-do” ability that forged this nation”.

The Adelaide Pound (Coins)

The Adelaide pound was part of the first Australian-made currency in 1852, with gold coins struck at the South Australian government assay office, Adelaide, using gold brought back from South Australian diggers’ finds in the Victorian gold fields. The currency the colony produced by South Australia was technically illegal as it hadn’t been approved in Britain but saved it the colony from bankruptcy.

South Australia’s 1840s copper boom was interrupted dramatically in 1851 by gold being discovered in Victoria. A third of South Australia’s men rushed off, taking a huge amount of gold sovereigns, causing a run on South Australian banks and hitting the economy.

South Australian governor Henry Edward Fox Young led a rescue mission. George Tinline, temporary manager of the South Australia Banking Company, convinced the government to place its money at the Adelaide banks.

A fixed price of £3/11/- an ounce for gold dust, more than the Victorian rate, was authorised by the government for all gold sent back to the colony by South Australian prospectors. To further attract guaranteed deliveries of gold to Adelaide, a monthly armed escort under zealous police inspector Alexander Tolmer was set up to bring the gold from Victoria. The first escort arrived at the government treasury building in Flinders Street, Adelaide city, in 1852.

To deal with the incoming gold, the South Australian government – at that stage, only operating with a Legislative Council – acted urgently and uniquely in Australian history. The Bullion Act No.1 was one of the quickest pieces of legislation ever passed, on January 28, 1852. The bill was read, promptly passed three readings and forwarded to the lieutenant governor, immediately received his assent – all in less than two hours.

Thirteen days later, on February 10, 1852, the government assay office opened at the treasury building. The ofice was effectively Australia’s first mint. Its sole purpose was to assay gold nuggets brought from the Victorian goldfields and reshape them into ingots.

But its work was unofficial because it was producing without British government permission or Queen Victoria’s approval. Its creators felt the time involved in gaining permission from London to set up a mint was too great a risk to the economy. To validate getting around royal protocols, South Australian legislators passed the Bullion Act by finding a loophole in regulations that allowed them to create their own mint and strike gold ingots.

The assay office melted and purified each prospector’s gold into a ingot stamped only with its weight. The banks issued certificates for the ingots as legal tender for 12 months. Within the first two weeks, deposits at the assay office totalled £24,000.

To fix issues with the unpopular ingots, the Bullion Act was amended nine months after it was passed (leaving only three months before it expired) to allow 10 shilling and £1, £2 and £5 gold pieces to be struck by the assay office. The office fortunately had engraver and die sinker Joshua Payne, only arrived in the colony in 1849, to do the coins’ intricate designs.

South Australia. British Colony – Victoria gold “Adelaide Assay Office” Ingot ND (1852) – Type I

Fr-4 (Rare), Rennik-pg. 20, 3, McDonald-pg. 40, Deacon-3 (R3). 15.58gm. Type 1. An unimaginably rare piece and one of only a handful not institutionally impounded, whose unassuming visuals are completely overshadowed by sheer historicity surrounding not only its creation but those that owned this very example. Among the smaller gold ingots we generally handle yet packing an impressive punch as a finely preserved specimen, likely the product of a keen collector having tucked away this piece not long after its issuance. Cast in a fairly crude manner with obverse text “WEIGHT OF INGOT” slightly off-planchet and stamped “10” indicating the pennyweight, a contemporary value of one Pound, seventeen Shillings, and one and one-half Penny. While the Government Assay Office of South Australia filled the need to process an influx of gold, this treatment proved impractical due to the varying weight and fineness of these ingots coupled with a general lack of circulating and standard currency. A mellowed rose-gold resplendence rests atop the present ingot, punctuated by lemon accents and gentle residual luster. While the occasional weakness and obfuscation occurs as a result stamping, this does little to detract from the overall appreciation of this momentous ingot. An amazing survivor that is expected to be among the sale’s most anticipated lots. Sold with the original Quartermaster Collection lot card.

Historical Owners

- Baron Philip Ferrari de La Renotiere Collection – Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge Auction, March 1922, Lot 693

- Virgil Brand (1922-1954) – Brand Journal #123453

- Farouk Collection (1954-1999) Sotheby’s February 1954, Lot 841

- John Jay Pittman Collection (1999-2009) – David Akers August 1999, Lot 4921

- Quartermaster Collection (2009-2023) – Monetarium, Australia June 2009, Lot 1

The ingot has been graded by NGC as MS63 and can be seen in the slab photos above. It is the only one graded by NGC at this time.

*** In 2009, it sold for $801,800 AUD.

[01/2023] https://coins.ha.com/itm/australia/australia-south-australia-british-colony-victoria-gold-adelaide-assay-office-ingot-nd-1852-ms63-ngc-/a/3105-32123.s ($540,000 USD)

Notes:

This Type I Ingot is the only known example of its type privately held.

A pentagonal cast of gold dug from the Victorian gold fields, struck on both sides. Maximum length 24.97mm, maximum width 23.73mm, thickness 2.3mm, weight 15.54 grams. Bullion Act Value £1/17/1.5. Sterling Value £2/0/8.5.

Obverse:

The Authority Stamp of a crowned ‘SA’ within a double linear shield is depicted on the obverse, made slightly indistinct by the reverse punching of the ingot weight. The word CARATS in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field. Below the numeral 23, also in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field, indicating a gold fineness of 23 carats.

Reverse:

The reverse is comprised of five lines of standard descriptive text. And two lines of technical information that specifies the weight of the Ingot.

- Line 1. Standard descriptive text, WEIGHT OF INGOT, curved along the planchet edge and slightly off planchet.

- Line 2. Standard descriptive text OZ . DWT . GR. with square stops in between.

- Line 3. 0 10 0, being the technical weight of the Ingot expressed in oz, dwt and grams.

- Line 4. The standard descriptive text EQUIV . WEIGHT with square stops in between.

- Line 5. The standard descriptive text OF 22 CARATS .

- Line 6. The standard descriptive text OZ . DWT . GRS with square stops in between partly obliterated by obverse punching.

- Line 7. 0 10 11, being the 22 carats equivalent Ingot weight expressed in oz, dwt and grams.

Provenance:

First recorded public sale at Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge London 27 – 31 March 1922, the property of Baron Philip Ferrari de La Renotiere. Acquired by Virgil Brand (USA) lot 693 for £185. Later became the property of King Farouk of Egypt. Sold as part of the Palace Collections of Egypt by Sotheby & Co London 1954 when it was acquired by Spink & Son London on behalf of John J Pitman. The J. J. Pitman Collection was sold in 1999 by David Akers Numismatics Inc., the Ingot acquired by Barrie Winsor on behalf of Australian collector, Tom Hadley.

Exhibitions:

This Type I Ingot was displayed in 2001 at the opening of the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, as part of an Exhibition of gold artifacts from around the world. The opening of the Museum was the centerpiece of Australia’s Centenary of Federation celebrations.

The Ingot was also displayed in 2001 at the Museum of Victoria.

It is difficult to be certain of how many ingots exist in total, but up to 8 may have survived, two of which have been “seen” for sale/auction in the past 100 years. The following table provides some context on those:

The table was built by Andrew Crellin and suggests that three type 1 and five type 2 ingots have been traced.

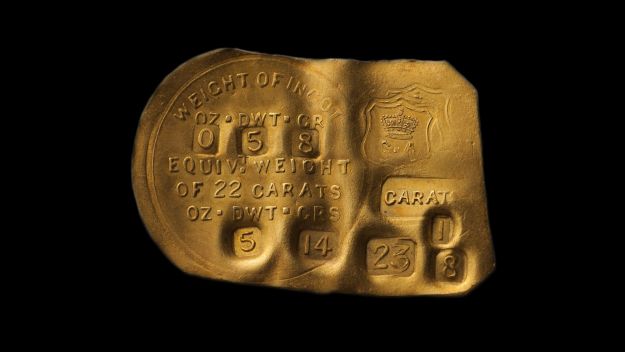

South Australia. British Colony – Victoria gold “Adelaide Assay Office” Ingot ND (1852) – Type II

This Type II Ingot is the only known example of its type privately held. Presented in a quality of Extremely Fine with technical reference J. Hunt Deacon 6.

A uniface oblong rolled gold Ingot, part rectangular with corners off. Struck on only one side. Maximum length 43.2mm, maximum width 27.6mm, thickness 1.2mm, weight 8.33 grams. Bullion Act Value £1. Sterling Value £1/1/11.

Obverse:

The Authority Stamp, a crowned ‘SA’ within a double linear shield, triple struck. The word CARATS in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field. Below, the numerals 23 and 1 over 8, also in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field, indicating a gold fineness of 23 1/8 carats.

To left, five lines of standard descriptive text. And two lines of technical weight information that specifies the weight of the Ingot.

- Line 1. Standard descriptive text, WEIGHT OF INGOT.

- Line 2. Standard descriptive text OZ . DWT . GR. with square stops in between.

- Line 3. 0 5 8, being the weight of the Ingot expressed in oz, dwt and grams.

- Line 4. The standard descriptive text EQUIV . WEIGHT with square stops in between.

- Line 5. The standard descriptive text OF 22 CARATS .

- Line 6. The standard descriptive text OZ . DWT . GRS with SQUARE stops in between.

- Line 7. 0 5 14, being the 22 carats equivalent Ingot weight expressed in oz, dwt and grams.

Reverse:

Blank.

Provenance:

First recorded public sale at Glendinings, London 21 – 23 November 1956, the property of Herbert W. Taffs M.B.E. Acquired for the Strauss Collection United Kingdom. Sold by private treaty in 1999 to Barrie Winsor on behalf of Australian collector Tom Hadley.

Exhibitions:

This Type II Ingot was displayed in 2001 at the opening of the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, as part of an Exhibition of gold artefacts from around the world. The opening of the Museum was the centrepiece of Australia’s Centenary of Federation celebrations.

The Ingot was also displayed in 2001 at the Museum of Victoria.